Canada's Indigenous peoples bring over 15,000 years of sophisticated business experience to modern economic partnerships, having created North America's first continental trading networks, sustainable resource management systems, and complex governance structures that continue to shape today's $60 billion Indigenous economy. This business-focused synopsis reveals why Indigenous nations represent experienced economic partners with proven resilience, sophisticated governance systems, and unique competitive advantages for corporate investors seeking sustainable, long-term value creation.

Understanding the deep historical foundations of Indigenous business acumen, governance structures, and legal frameworks is essential for corporate leaders navigating modern partnership negotiations. Indigenous communities aren't learning business—they invented many of its fundamental principles on this continent. Their traditional systems of consensus-based decision-making, sustainable resource management, and long-term strategic planning offer proven models that align remarkably with contemporary ESG investment criteria and stakeholder capitalism principles.

The convergence of constitutional protections, Supreme Court decisions recognising Indigenous title, UNDRIP implementation, and a rapidly growing Indigenous economy creates unprecedented partnership opportunities. With 95% of critical mineral projects and 44% of Canada's best renewable energy sites located on traditional Indigenous territories, corporate success increasingly depends on understanding and respecting Indigenous governance systems, legal rights, and business approaches rooted in millennia of experience.

Pre-contact trading empires demonstrate continental business sophistication

Indigenous peoples operated North America's first multinational corporations, managing trade networks that spanned from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from the Arctic to central Mexico. Archaeological evidence reveals the extraordinary scale of these operations: native copper from Lake Superior found in Louisiana, mother-of-pearl from the Gulf of Mexico discovered in Manitoba, and obsidian from Mexico's Valley of Hidalgo traded to Oklahoma. The Spiro trading centre (900-1450 AD) controlled continental commerce with sophisticated infrastructure, including established trade languages, quality standards, transportation networks, and financial systems.

These weren't primitive barter systems but complex market economies. Indigenous nations created the 20,000-mile road network that connected trading centres, developed common trade languages like Chinook Jargon used from Alaska to California, and established quality control standards that would be familiar to any modern supply chain manager. As Indigenous business expert C.T. Jules emphasises, "Market economies are not foreign to us. We created them ourselves. Trade cannot be financed without capital. We had to build transportation methods such as boats, large public buildings, and maintain armies to provide order."

The potlatch system of the Pacific Northwest exemplifies this business sophistication. Far from simple gift-giving ceremonies, potlatches functioned as complex financial institutions combining elements of banking, insurance, venture capital, and property rights enforcement. These elaborate economic gatherings redistributed wealth, managed risk across communities, provided investment capital for major undertakings, and established enforceable property rights over territories and resources—all while maintaining detailed oral records of transactions and obligations that courts now recognise as valid legal evidence.

Traditional governance systems inform modern consultation requirements

Understanding Indigenous governance structures is crucial for corporate leaders because these systems directly shape current consultation requirements and partnership negotiations. Traditional Indigenous governance wasn't primitive or simplistic—it featured sophisticated checks and balances, complex decision-making processes, and sustainable resource management systems that operated successfully for thousands of years.

Traditional First Nations governance systems varied by region but shared common elements that persist today. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy's three-tier political system included village councils, tribal councils, and a confederacy council, all operating on a consensus basis with discussions "often going late into the night until everyone reached agreement." The Anishinabek system featured three distinct consultation circles: Women's and Children's Circles (considering impacts on future generations), Elders' Circles (providing historical context), and Men's Circles (addressing immediate needs). These structures explain why modern consultation takes time—decisions require broad consensus and consideration of long-term impacts.

Today's dual governance reality creates complexity but also opportunity. Many communities operate under both the federally imposed band council system and traditional hereditary leadership. As one expert notes: "For Industry to achieve an agreement with Indigenous communities, typically, hereditary chiefs, matriarchs, and elected chiefs and councils will need to be consulted." Successful partnerships like Suncor's Thebacha venture ($1.2 billion with Fort McKay and Mikisew Cree) demonstrate that understanding and respecting these governance systems leads to stronger, more sustainable agreements.

Constitutional protection and evolving legal frameworks establish partnership imperatives

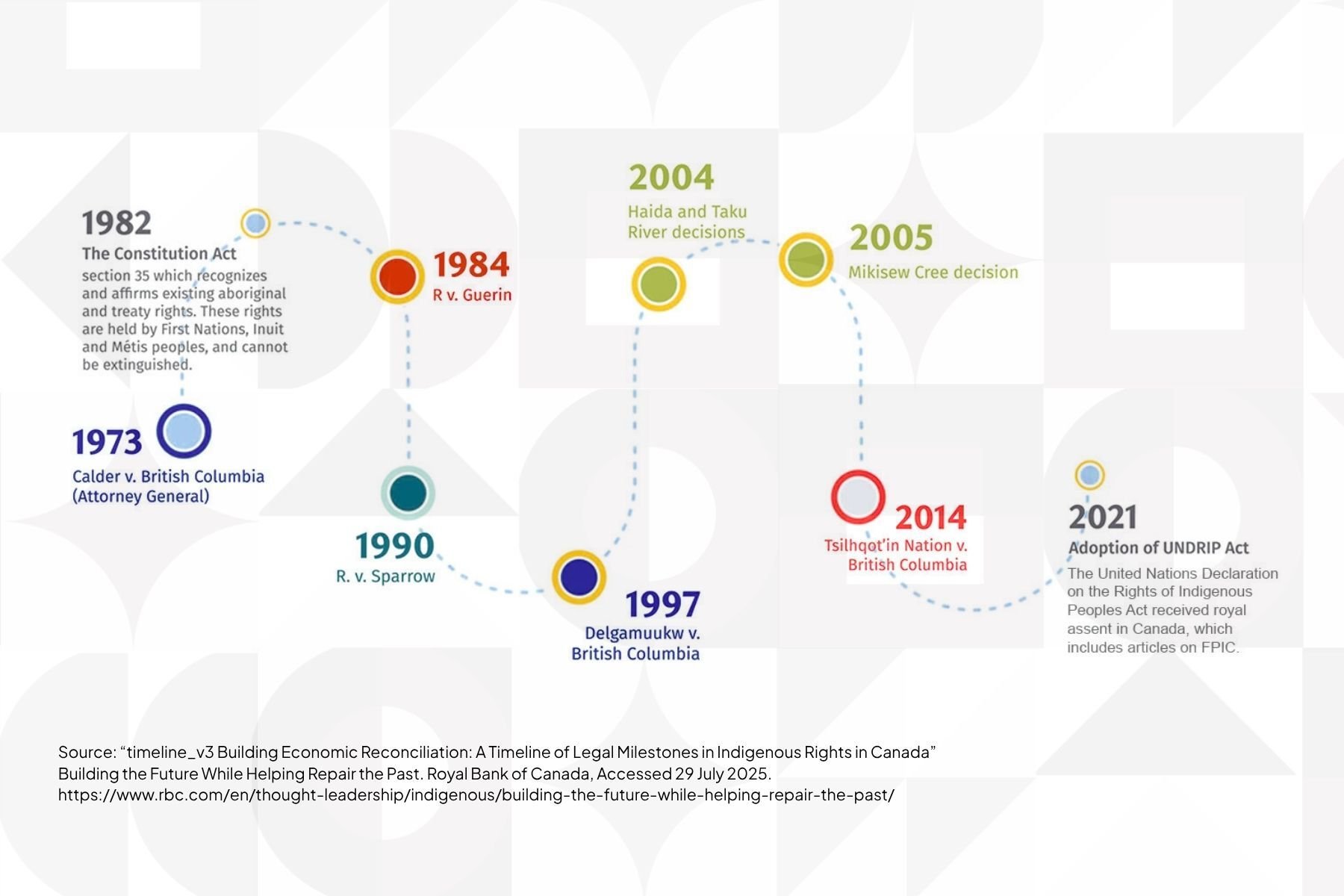

Canada's legal framework has fundamentally transformed Indigenous-corporate relationships from stakeholder management to rights-holder partnerships. Section 35 of the Constitution Act (1982) provides ironclad protection for Aboriginal and treaty rights that cannot be extinguished unilaterally by any government. This constitutional shield, combined with landmark Supreme Court decisions, creates both obligations and opportunities for business.

The Tsilhqot'in decision (2014) marked a watershed moment, establishing that courts can declare Aboriginal title over traditional territories beyond reserve boundaries. This grants Indigenous nations exclusive ownership rights and control over economic benefits from their lands. For resource companies, this means traditional territories are no longer simply Crown land available for development—they may be Indigenous-owned lands requiring consent, not just consultation.

The duty to consult exists on a spectrum from basic notification for minor impacts to deep consultation potentially requiring accommodation or consent for major projects affecting strong Indigenous claims. The Haida decision (2004) clarified that while consultation doesn't grant veto power, meaningful engagement is mandatory. Smart companies have discovered that exceeding minimum legal requirements by pursuing genuine partnerships yields competitive advantages: faster regulatory approvals, reduced litigation risk, enhanced social license, and access to traditional knowledge that improves project outcomes.

Traditional knowledge systems offer competitive advantages in sustainable business

Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) represents validated intelligence from thousands of years of environmental observation and sustainable resource management. With Indigenous peoples stewarding 25% of global land surface while supporting 80% of biodiversity, their knowledge systems offer proven pathways to sustainability that modern science is only beginning to understand.

TEK provides immediate business value across sectors. In forestry, traditional controlled burning reduces wildfire risk while enhancing biodiversity and carbon sequestration. In fisheries, Indigenous selective harvesting techniques maintained salmon populations for millennia—knowledge now being applied to restore depleted stocks. In mining, traditional impact assessment methods and restoration techniques reduce environmental risks and improve closure outcomes. The seven-generation thinking principle, requiring consideration of impacts 140-200 years into the future, aligns perfectly with long-term value creation sought by ESG-focused investors.

Companies integrating traditional knowledge gain measurable advantages. The Iowa Tribe's CERNA Initiative secured USDA climate-smart commodities funding by demonstrating how traditional agricultural practices enhance carbon sequestration. Shinnecock Kelp Farmers, six Indigenous women entrepreneurs, created a sustainable business model that provides carbon credits while restoring marine ecosystems. These aren't quaint cultural practices but sophisticated technologies validated through centuries of successful application.

Historical resilience through adaptation demonstrates reliability as long-term partners

Indigenous nations' ability to adapt and thrive through dramatic historical disruptions demonstrates the resilience that makes them reliable long-term business partners. Despite facing colonisation, the Indian Act's restrictions on economic activity, residential schools designed to destroy culture, and systematic exclusion from the mainstream economy, Indigenous peoples maintained their business acumen and cultural integrity.

During the fur trade era, Indigenous nations weren't passive suppliers but active partners who controlled trade routes, set terms, and played European companies against each other for better prices. The Métis emerged as specialised entrepreneurs, developing transportation networks and cross-cultural business expertise that made them indispensable to the continental economy. Even under the Indian Act's severe restrictions, Indigenous communities created innovative corporate structures and maintained traditional economic knowledge.

This historical resilience translates into contemporary business strength. Indigenous businesses are being created at five times the rate of non-Indigenous businesses. The Indigenous economy grew 74.7% between 2012-2022, compared to 54% for the broader Canadian economy. Indigenous-held jobs increased 29.7% versus 12.2% nationally. This isn't catch-up growth—it's the continuation of entrepreneurial traditions that predate European contact.

Contemporary economic development creates immediate partnership opportunities

Today's Indigenous economy represents a $60.2 billion force growing at 9.8% annually, consistently outperforming national averages. Over 50,000 Indigenous-owned businesses employ 886,000 people, with Indigenous Financial Institutions managing $3.3 billion in loans while maintaining a remarkably low 2.1% loss rate. The sector is projected to reach $100 billion by mid-decade.

Modern success stories demonstrate sophisticated business capabilities. Fort McKay Group of Companies operates multi-billion-dollar enterprises in oil sands and environmental services. The Thebacha Partnership's 49% Indigenous equity stake in Suncor's East Tank Farm represented the largest Indigenous business investment in Canadian history. The 2022 Athabasca Indigenous Investments transaction with Enbridge, involving 23 First Nations and Métis communities in a $1.12 billion deal, showcases the scale of contemporary Indigenous investment capacity.

The Indigenous Growth Fund, with $153 million in committed capital from institutional investors, including the federal government and major corporations, provides expansion capital for Indigenous businesses. Federal procurement policies mandating 5% of contracts go to Indigenous businesses created $1.24 billion in opportunities in 2023-24 alone. With Indigenous communities strategically positioned near 95% of critical mineral deposits and 44% of optimal renewable energy sites, partnership opportunities span every major economic sector.

Strategic pathways forward capitalise on historical foundations

Understanding Indigenous history transforms how corporate leaders approach partnerships. This isn't corporate social responsibility or reconciliation charity—it's recognising Indigenous nations as sophisticated economic actors with unique competitive advantages. Their governance systems, rooted in consensus-building and long-term thinking, create more stable, sustainable agreements. Their traditional knowledge provides proven solutions to modern sustainability challenges. Their demonstrated resilience ensures they'll remain reliable partners through economic cycles.

Successful partnerships require respecting historical governance systems by engaging all appropriate authorities, allowing adequate time for consensus-based decisions, and understanding that quick deals often become failed deals. Engineers Canada Companies must recognise that Indigenous partners bring not just land access but sophisticated business knowledge, proven sustainable practices, and governance models aligned with stakeholder capitalism.

The legal framework—from Section 35 constitutional protection to UNDRIP implementation—creates clear partnership imperatives. Wikipedia +5 But the business case transcends compliance. Indigenous partnerships provide access to critical resources, traditional knowledge that enhances project success, stable long-term relationships, and alignment with ESG investment criteria. As one Indigenous business leader notes, "We're not asking for handouts. We're offering partnerships based on 15,000 years of business experience on this land."

Corporate leaders who understand this history recognise that Indigenous nations aren't learning capitalism—they helped invent it on this continent. Their sophisticated trading networks, sustainable resource management, consensus governance, and proven resilience make them ideal partners for creating long-term value in an increasingly complex, sustainability-focused economy. The question isn't whether to partner with Indigenous nations, but how quickly corporate Canada can embrace these opportunities rooted in the deepest business history of this land.