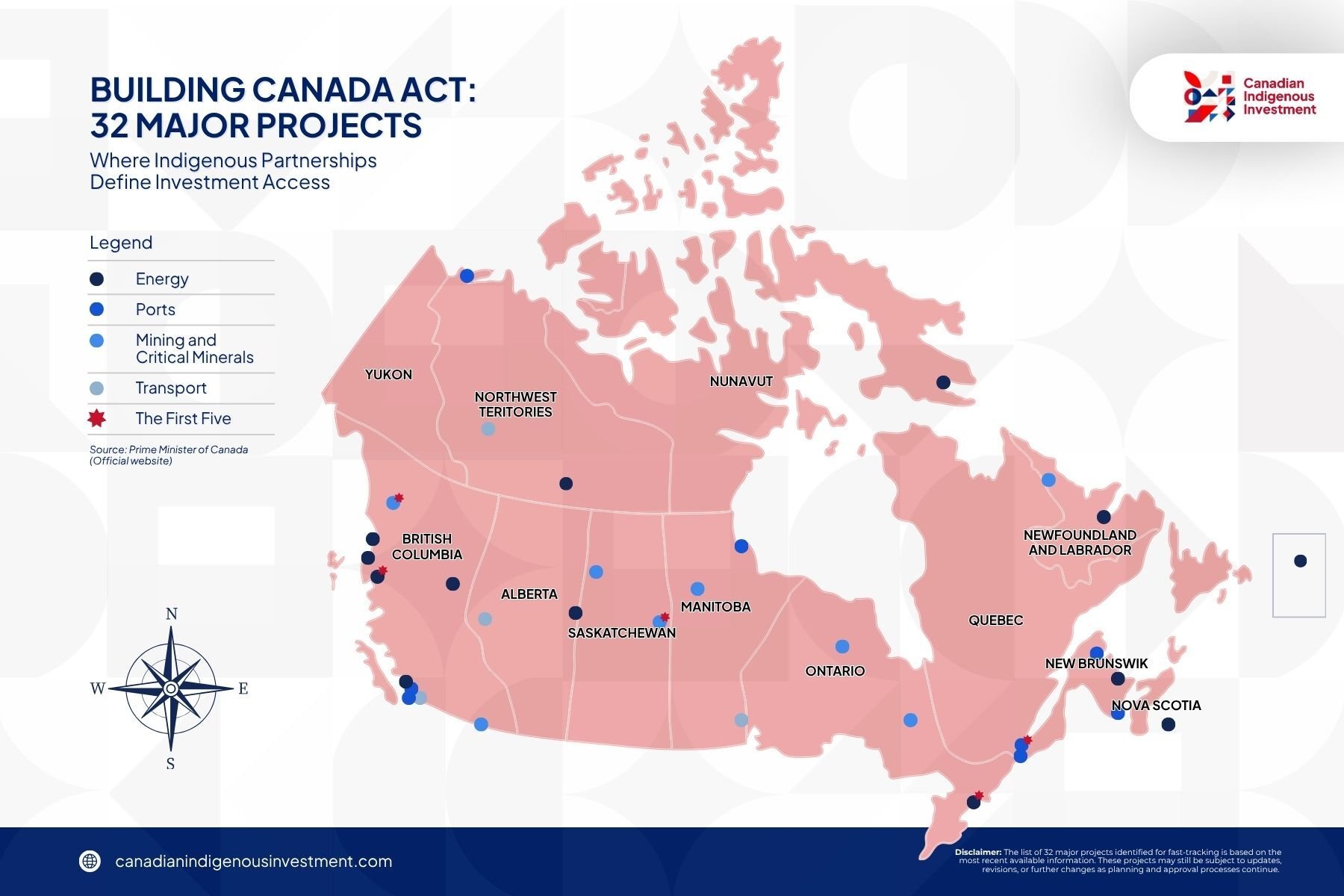

Canada's federal government has drafted 32 major infrastructure projects under the Building Canada Act1, reviewed for fast-track considerations. The first group of projects is valued at more than $60 billion, showing Canada’s strong focus on clean energy, economic resilience, and Indigenous partnership. Each project supports a stronger, more sustainable future for northern and regional development.

Together, these 32 projects show how Canada is investing in modern infrastructure, creating jobs, and promoting sustainable growth while working closely with Indigenous communities.

The 32-project portfolio encompasses energy corridors connecting Alberta resources to Asian markets, critical minerals developments in territories under Indigenous land claim agreements, Arctic infrastructure where Indigenous communities control access rights, and trade gateway facilities requiring consultation under historic treaty frameworks. Projects without authentic Indigenous partnership structures face material completion risks that traditional infrastructure analysis systematically underestimates.

Investment Structure Reality: Energy Corridors and Indigenous Consent

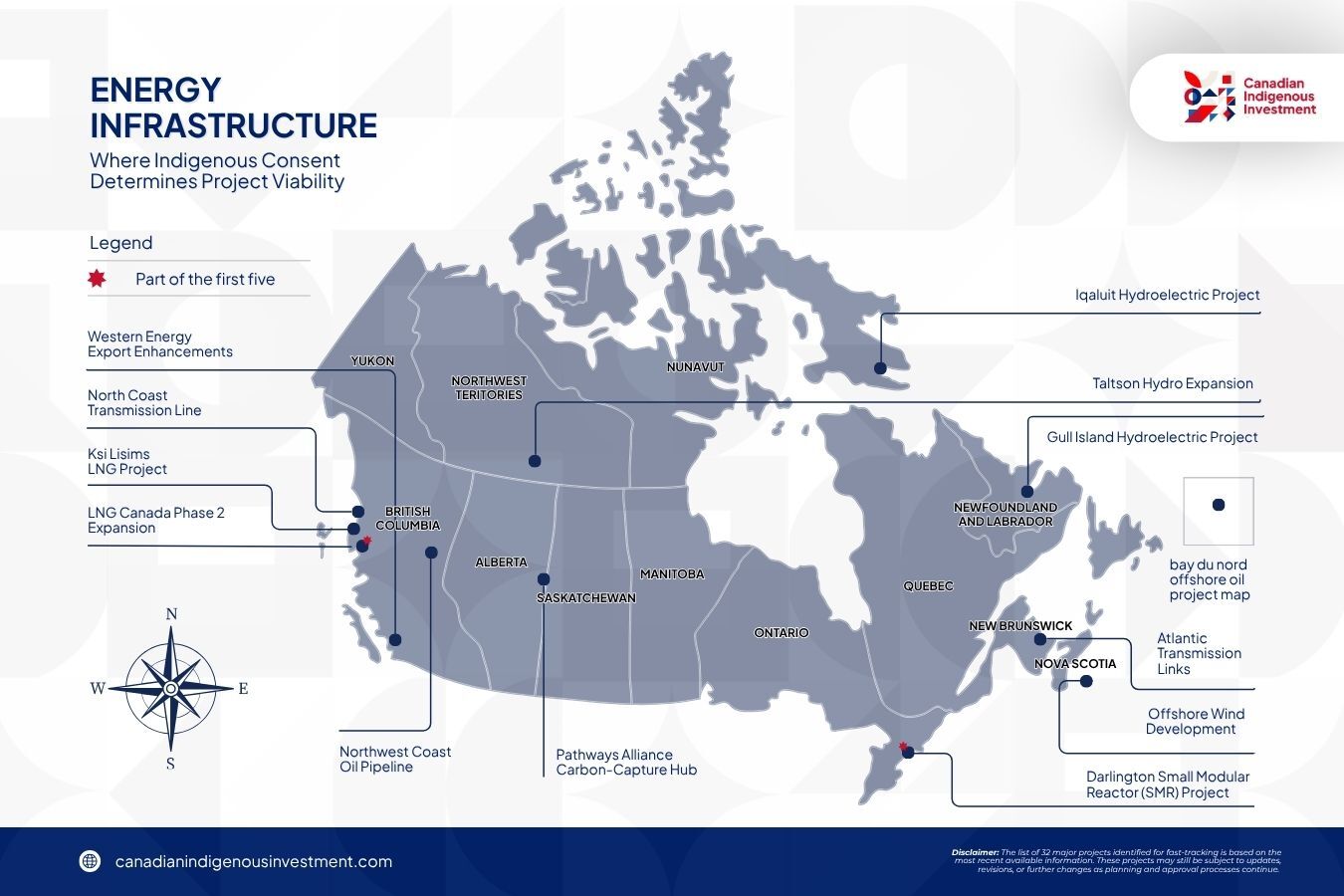

The proposed Northwest Coast Oil Pipeline from Alberta to British Columbia illustrates how Indigenous consent frameworks now determine project economics rather than simply regulatory timelines. Alberta's provincial government supports the corridor to connect landlocked oil resources to Asian markets, viewing it as essential economic infrastructure. Yet several British Columbia First Nations and the provincial government have indicated opposition, creating investment risk that extends beyond traditional permitting analysis. Premier Danielle Smith stated in September 2025 that she's working with oil companies on the pipeline proposal and remains confident she can convince BC Premier David Eby of its merits, yet no Indigenous partnership structure has been announced.

The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion (completed in 2024 under federal ownership) required seven years and $34 billion2 , driven largely by extended Indigenous consultation processes rather than engineering complexity. Projects succeed or stall based on Indigenous community support, regardless of government enthusiasm or commodity market demand.

Projects with meaningful Indigenous involvement often experience more defined progress. The Ksi Lisims LNG project near Kitimat, which includes Nisga’a Nation equity participation in the terminal and the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission pipeline, reflects this growing model of collaboration. The Nisga'a partnered with Houston-based Western LNG and purchased the pipeline project from TC Energy in June 2024, creating an Indigenous-controlled supply chain. LNG Canada Phase 2 (also near Kitimat, announced as a Major Projects Office priority in September 2025) operates under Indigenous benefit agreements negotiated during Phase 1, which began exporting in June 2025, providing regulatory certainty unavailable to projects lacking Indigenous support.

The investment implication: due diligence protocols must assess Indigenous partnership quality as rigorously as technical feasibility or commodity pricing. Projects with Indigenous equity participation demonstrate materially lower regulatory risk profiles than those relying on benefit agreements alone or facing community opposition. This represents fundamental investment dynamics unfamiliar to European investors accustomed to jurisdictions where government permits determine project viability.

Project Portfolio Analysis: Indigenous Partnership Patterns Across Sectors

The 32 projects reveal distinct Indigenous partnership patterns across four infrastructure categories, providing UK and European investors with strategic intelligence for portfolio positioning.

Energy Infrastructure: LNG Canada Phase 2 in Kitimat (announced September 2025 as a Major Projects Office priority, expected to attract $33 billion3 in private capital and double Canada's LNG export capacity) operates under existing Indigenous agreements negotiated during Phase 1. Ksi Lisims LNG backed by the Nisga'a Nation represents majority Indigenous ownership with equity in both the 12-million-tonne-per-year facility and supply pipeline, accessing federal Indigenous Loan Guarantee Programmes.

Alberta's Pathways Alliance carbon capture and storage project faces consultation requirements with Treaty 6, 7, and 8 First Nations covering oil sands regions. Ontario's $20.9 billion small modular reactor programme at Darlington (announced as a Major Projects Office priority, expected to make Canada the first G7 country with operational SMR technology) and multiple Northern hydro projects each navigate different Indigenous land claim frameworks based on treaty structures and territorial claims.

Critical Minerals Development: Teck Resources' Strategic Minerals Initiative builds on existing relationships with Ktunaxa and Secwepemc Nations in British Columbia, demonstrating how established partnerships enable project advancement. Red Chris Copper expansion in northwest British Columbia (announced as a Major Projects Office priority in September 2025) operates through partnerships with Tahltan Nation.

Foran Mining's McIlvenna Bay copper project in Saskatchewan (also a Major Projects Office priority) demonstrates early Indigenous engagement protocols. Ontario's Ring of Fire chromite development remains the most significant critical minerals opportunity yet is contingent on resolving benefit-sharing agreements with Matawa First Nations, who have maintained that individual community agreements do not constitute collective consent for mineral development.

Port and Coastal Infrastructure: Churchill (Manitoba) expansion on Hudson Bay holds strategic significance for Arctic shipping routes and Prairie grain exports, requiring consultation with multiple Dene and Inuit communities. Port of Montreal's Contrecoeur terminal expansion (announced as a Major Projects Office priority, expected to increase capacity by 60%) navigates historic treaty consultation requirements. Port of Vancouver dredging to accommodate fully loaded oil tankers in Burrard Inlet crosses Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nation territorial waters. Port of Saint John expansion in New Brunswick and Yellowknife's proposed deep-water Arctic port each operate under different Indigenous consultation frameworks based on regional treaty structures.

Transportation Infrastructure: Mackenzie Valley Highway connecting Northwest Territories resources to southern markets requires agreements with multiple Dene and Métis communities whose traditional territories the route crosses. Trans-Canada Highway twinning addresses capacity constraints but faces varying consultation requirements based on specific route segments.

New Westminster Rail Bridge rehabilitation in British Columbia involves consultation with multiple coastal First Nations. The Alto high-speed rail corridor between Toronto and Quebec City (announced as a Major Projects Office focus, estimated $35 billion construction cost with potential to create 51,000 jobs) crosses numerous First Nation territories, requiring extensive consultation protocols.

Understanding these sector-specific partnership patterns enables investors to assess which opportunities offer clearer paths to development versus those requiring extended negotiation periods. Projects with demonstrated Indigenous equity participation consistently show faster advancement than those relying solely on consultation protocols without ownership structures.

Accelerated Framework and Indigenous Consultation Requirements

Bill C-5 (the One Canadian Economy Act) received Royal Assent on 26 June 2025, establishing the Building Canada Act framework. Projects deemed in the national interest are not being reviewed through the new Major Projects Office, headquartered in Calgary and led by Dawn Farrell, former Trans Mountain pipeline CEO. Farrell's appointment in August 2025 signals federal recognition that Indigenous consultation represents the primary determinant of major project completion timelines. Her direct experience navigating Trans Mountain's Indigenous partnership requirements during the expansion's completion provides operational expertise relevant to the Major Projects Office mandate.

The streamlined process reduces certain regulatory timelines, with Prime Minister Mark Carney directing the Major Projects Office to ensure all major projects receive review within two years maximum (compared to five or more years previously). However, the legislation explicitly maintains Indigenous consultation obligations throughout the process, reflecting Ottawa's recognition that Indigenous opposition represents the primary obstacle to major project completion rather than federal regulatory complexity.

The framework creates a two-tier project landscape. Projects with Indigenous partnerships advance quickly through the Major Projects Office single-window review process, accessing coordinated federal support and "one project, one review" approaches negotiated with provinces. Projects facing community opposition encounter extended timelines regardless of technical merit, commodity market demand, or federal government enthusiasm. This creates material completion risk invisible to conventional infrastructure analysis.

Capital Requirements and Indigenous Investment Structures

The investment landscape in Canada is changing. More projects now give Indigenous communities real ownership instead of short-term benefits. This approach shows a growing understanding that meaningful participation builds trust, improves results, and supports long-term economic stability for both Indigenous and industry partners.

Recent data from the legal firm Fasken shows this shift clearly. Around 78 percent of announced Indigenous equity investments now include 50 percent or more Indigenous ownership. This means most projects are now equal or majority partnerships instead of traditional benefit agreements. The data covers 135 energy and infrastructure projects over the past 15 years. Almost 30 percent of those investments happened in just the last two years, showing strong growth in Indigenous participation.

This trend connects to the 32 major infrastructure projects now moving forward across Canada. Many of these projects, such as energy corridors, port expansions, transportation upgrades, and critical minerals development, are located in or near Indigenous lands. Because of this, Indigenous ownership and involvement are now central parts of planning, funding, and construction.

For investors, success depends on building early partnerships with Indigenous governments and development groups. Equity participation is becoming a key step in gaining community support and access to land and permits. These 32 projects represent a new model of shared growth that combines national goals with Indigenous economic leadership.

Western Trade Corridor Integration and Indigenous Land Access

The Western Trade and Economic Corridor concept connects transportation infrastructure, energy pipelines, and electrical transmission across Western Canada to Pacific ports, positioning Canadian resources for Asian and global market access. The corridor's viability depends entirely on Indigenous partnerships rather than government planning alone. Indigenous communities control access rights across much of the proposed route through treaty territories, modern land claim agreements, and unceded lands where Aboriginal title has never been extinguished through treaty or other legal means.

Ottawa's approach attempts to balance traditional resource development with clean energy transition, supporting both LNG exports and carbon capture initiatives whilst funding small modular reactors and Northern hydroelectric development. This policy direction reflects political necessity (Western provinces depend on resource revenues for fiscal sustainability) and economic pragmatism (global demand for Canadian energy and minerals continues regardless of domestic policy preferences). The Building Canada Act explicitly positions Canada as both a conventional and clean energy superpower, acknowledging market realities rather than prioritising one energy source over others.

Constitutional protections for Indigenous rights (section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982) create legal obligations that supersede provincial resource jurisdiction, fundamentally altering risk profiles compared to jurisdictions where government permits provide sufficient project certainty.

Success indicators centre on early Indigenous equity participation and comprehensive benefit-sharing agreements rather than government milestones. Projects demonstrating Indigenous ownership structures show materially higher completion probabilities than those relying on consultation protocols without equity components. The Northwest Coast Oil Pipeline proposal exemplifies high execution risk (Alberta government support but BC and First Nations opposition), whilst Ksi Lisims LNG exemplifies lower regulatory risk through Indigenous equity participation and community backing.

Investment Implications

The 32 projects identified under the Building Canada Act reflect key national infrastructure priorities, emphasising that the strength of Indigenous partnerships will play a major role in determining their investment potential rather than relying solely on government endorsement. The project list remains provisional, with final selection following Indigenous consultations throughout 2025. Prime Minister Carney announced the second tranche of projects would be finalised before the Grey Cup in November 2025, with additional announcements expected through year-end. Projects advancing to federal funding and Major Projects Office support will be those successfully negotiating community backing, creating a natural selection process favouring authentic Indigenous partnerships over performative consultation exercises.

The opportunities exist not simply in identifying promising projects based on commodity demand or technical specifications, but in assessing which projects have secured the Indigenous support necessary for completion. Ontario's Ring of Fire minerals development demonstrates this dynamic: despite an estimated $60 billion CAD resource value and decade-long provincial government enthusiasm, the project remains contingent on unresolved Indigenous consultation issues. Conversely, projects like Cedar LNG (Haisla Nation majority ownership) and Ksi Lisims LNG (Nisga'a Nation equity participation) advance through regulatory processes based on Indigenous partnership structures rather than government advocacy alone.

Canada's constitutional framework creates investment dynamics fundamentally different from jurisdictions where government permits provide sufficient project certainty. Section 35 of the Constitution Act recognises and affirms Indigenous rights, creating Crown obligations to consult and accommodate Indigenous peoples whose rights may be affected by development. Courts have consistently affirmed that these obligations cannot be bypassed through regulatory fast-tracking. The Building Canada Act recognizes this by retaining consultation requirements even as it seeks to accelerate other aspects of the review process. Understanding these partnership dynamics provides market intelligence unavailable through conventional infrastructure analysis, enabling informed assessment of which Building Canada Act projects carry realistic completion prospects versus those facing material Indigenous opposition risks.

1 i https://www.canada.ca/en/one-canadian-economy/services/building-canada-act-projects-national-interest.html↩ Back

2 i https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/trans-mountain-expansion-begins-1.7150343#:~:text=Calgary-,$34B%20Trans%20Mountain%20expansion%20pipeline%20begins%20filling%20with%20oil,pipeline%20begin%20filling%20with%20oil.↩ Back

3 i https://natural-resources.canada.ca/energy-sources/powering-canada-forward-building-clean-affordable-reliable-electricity-system-every-region-canada↩ Back